Virginia Lee Burton is the author of many well loved books for children, including Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel and The Little House. In the picture book, Life Story, written in 1962 she sets out to tell “the story of life on our earth from its beginning up to now”. She sets up the timeline of

prehistory as a play on a stage and moves us from the introduction of our galaxy in the prologue into Act I - the Paleozoic Era, with scenes of Life in the Cambrian seas, the Ordovician seas, the Silurian shores the Devonian shores and on to the Carboniferous swamps and the Permian desert. The story continues with four more acts that cover the Mesozoic Era, the Cenozoic Era and eventually on to the Life of Prehistoric man right up to recent times. This book was the major touchstone for the Lake and Park study of prehistory.

It didn’t take long before the names of these different eras were rolling off the tongues of children

throughout the school. Teachers were paying close attention to which details were grabbing the

attention of different individuals. Children began rendering different eras in paint and pastel as they

wondered about different aspects of life on earth during different time periods. This period of

exploration early in a study is often open-ended, encouraging children to make connections and

express ideas in a safe and supportive environment. It allows children the time to find their own

way into a study, to begin to construct meaning. As we design and plan curriculum we create

opportunities for diverse learners to enter into a study.

The Very Beginners work as paleontologists, the Beginners observe bones and

carefully sketch the shapes as they wonder about the discovery of dinosaur bones.

The Big Room students are guided through an initial exploration of geological

time. Before contemplating the timeline, the North Room students took time to go outside and reflect on what they already knew and what they thought about where humans came from.

Eventually different classes found the era or topic within the larger study of prehistory on which to focus their research.

The Very Beginners and Beginners focused on the Permian Period of the Paleozoic Era, about

235,000,000 years ago and into the Mesozoic Era (Middle life) including the Triassic Period, the

Jurassic Period and the Cretaceous Period up to about 60,000,000 years ago. This met the

developmental needs of children ages 3 -6.

Many parents have experienced their children’s love of dinosaurs. The importance of this interest is backed up by research from the University of Indiana, which found “that sustained intense interests, particularly in a conceptual domain like dinosaurs, can help children develop increased knowledge and persistence, a better attention span, and deeper information-processing skills. In short, they make better learners and smarter kids.”

|

| Beginning Room children build dinosaur sculptures with big blocks. |

|

| Beginning Room children role- play working as paleontologists. |

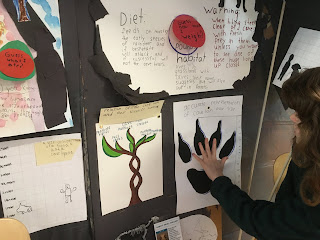

Cenozoic Era. This was after the dinosaurs died out from about 40,000,000 years ago right up to 10,000 years ago. Each child researched a particular animal and created an exhibit to share their work with the larger community.

|

| After choosing an animal to research, students got to know them from the inside out. |

|

| They learned about their individual animal in the context of the other animals classmates were learning about. |

helped us better understand life on earth long ago. We hosted an archaeologist and a

paleontologist at school. Some classes visited the Primate Evolutionary Biomechanics Laboratory at

UW and met with anthropologists. Everyone spent time with a group of flint knappers, who continue

to study and recreate early human stone tools. Our final field work was a day spent at the new

Burke Museum where the labs are all visible to museum goers. When children are exposed to

adults who work in the field we are studying they make the connection that these topics are relevant

and the work we are doing is important.

|

| Siobhan Brown, parent of Declan shared her experience as an archaeologist. |

|

| Tom Wolken, president of the Northwest Paleontological Society visited Lake and Park and spoke to each class in a smaller setting. |

|

| The Puget Sound Knappers set up a workshop for Lake and Park students at one of the shelters at Seward Park. |

|

| Working at the Burke Museum. |

The North Room students (ages 9-12) narrowed their study to consider the evolution of humans

during the Quaternary Period of the Cenozoic Era from about 25,000 to 10,000. In addition to the

many scientists the North Room students talked with they also spent some time with Merna Hecht,

an artist-in-residence, learning about the art of storytelling. While researching a particular

aspect of early human development, they also transformed their classroom into a cave, covering the

walls with cave paintings, building a sculpture of a fire hearth and inviting the community to hear

stories told the way humans have shared stories since speech was developed.

|

| Merna coaches the students on traditional storytelling techniques. |

The study of Prehistory was scheduled to accompany the opening of the new Burke Museum. It was

a way to prepare us for a first visit to the museum and to be fully present for its opening. It was natural for us to want to share our enthusiasm for the new museum by opening our

own Lake and Park School Prehistory Museum. We invited the larger community to come to the

museum and students acted as both museum guides and as visitors. Children felt honored to share

what they had learned with guests.

|

| Parents,grandparents, neighbors and children all gather to experience a story in the North Room cave. |

|

| One of many exhibits in the museum. |

|

| Big Room students created a special ice age exhibit to house the early mammal displays. |

|

| Gus shares his exhibit with his family during the museum. |

|

| Morgan helps students prepare for their different jobs at the museum. |

|

| Japhy and his dad visit exhibits and fill in the museum guide. |

|

| These bones add some realism to an exhibit about the diet of early hominids. |

|

| Noe compares the size of her hand to the actual size of the paw of the cave lion. |

|

| In addition to dioramas about a particular dinosaur, Beginning students also created wooden dinosaur sculptures. |